While driving home after a long day of work, I caught myself frowning–like seriously frowning. My shoulders are knotted and my hands gripping the wheel tightly. I’ve been up since four am, I’m hungry, tired and annoyed by traffic, drivers and the birds flying around, looking so god damned free. Oh my god, I have got to relax–quick reality check, the sun is shining, I’m on my way home, and as if to prove that all was about to get better, “Mushaboom” by Feist played on CBC 2. This song is so happy and hand-clappy and just breaks my heart with the cuteness. The song is about building a life with your lover on a limited budget: “I got a man to stick it out/ And make a home from a rented house/ And we’ll collect the moments one by one/I guess that’s how the future’s done”. Okay…exhale. I roll the window down and chimed in. I arrived home before the song ended, and I just took a moment in the parking lot before I headed inside. This is a common action, to just sit in the car and hear a song out, like the closing arguments in a court case. Its also about trying to leave stress of a work day behind…the day is done, it doesn’t matter anymore. The song is about not being ‘there’ yet…but making that place in between your home. After all: “It may be years until the day/ My dreams will match up with my pay”. It feels like it sometimes, like your station in life will never improve, or success will happen when you are so old, you have to spend your fortune on Botox due to the craggy lines that have burrowed into your face from all the hard work and post-work scowling.

I have had many jobs that did not suit my temperament–sometimes in the thick of the drudgery, worn down by the grind, I’ve felt like a caged songbird who has forgotten how to croon, and something inside of me dies a little. Surely I was meant for more than this. I have a friend who works at a liquor store, and he was telling a co-worker how he was doing the job until he finished university and got a real job–”Oh, that’s what I said, but I’ve been here a few years now”. And there was something about this person’s casual landslide from means-to-an-end to career made my friend rather insistent, like a prisoner in solitary confinement arguing with a mouse: “No, really…I’m going to get out of here–just you wait and see”. “Sure kid…that’s what they all say…every one here is just passing through”. (why do I imagine this mouse chewing on a little tiny toothpick menacingly?).

When we lived in Australia, my work visa limited me to a minimum of six months to one job. I waitressed at a posh spot along the waterfront, serving Perth’s upper crust businessmen and political figures. The job was fine, and the pay was excellent, but the hours were terrible. But I was good at the job–I am a very good waitress. But I’m good for the work in the same way you pump change into a meter and after a brief period, the allotted time runs out. Around the time I told a customer that she “wasn’t going to die if she had to wait for her chardonnay”, my six months were nearly up, and I got a job working on the same construction site as my husband. As a magnificent stroke of luck, the site–a brand new apartment complex was a mere block away from our flat, and every morning we’d walk to work, our hard hats in hand–and in the middle of a staggeringly hot summer, we’d skip home at lunch and go swimming.

As cleaner, my job was to take dusty, filthy suites, strip the protective plastic layers off every surface. All I had to do was avoid empty bottles filled with urine–which was an issue–work quickly, and I could make hundreds of dollars a day. To save up for our holidays, Ben and I worked long hours, usually six days a week. I worked alone, and would go long periods without seeing another soul, which I loved. I would listen to the radio, rush about the finished suites, and daydream. I was like a steel-toed Roxy Hart in Chicago, while I was filthy and exhausted, I was elsewhere in my mind.

Most importantly, I was a contractor on a piece rate, and there was nobody to micro-manage me. There was about five women amongst the hundred or so men; the other cleaners were nice ladies, called me ‘love’ or ‘bub’. I didn’t see them often, they chose to work on hourly-rate and mostly spent their days looking for windows to smoke out of. Everybody smoked on this job site, it was like “Mad Men” with tool belts. To get into the building, you’d have to ride the alimak, meaning that if this elevator was a belly button, it would be an outtie, not an innie. At first the novelty surpassed the cigarette smoke and stench of unwashed men. (How this combination has not been made into some celebrity fragrance is beyond me), but I very quickly lost patience with the ride, and so I took the stairs up to my floor, some twenty five flights up…three times a day. What an incredible slog, that journey each day, hiking the dingy staircase, climbing upwards to eternity. Like being on small planes makes me think of Buddy Holly, this made me think of Sisyphus–the King sentenced to push a giant boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down; and he would repeat this action forever. No six month visa limitations on that shit y’all. I came to think of Sisyphus on each and every climb. What a shitty deal that would be–maybe you’d have a good body from all that hard work, but what would happen if you met someone? (“So, where’s your family from? Ooops, hold that thought, I’ve got to push this boulder up this hill, be back in a jif”)

For a while, things were ticking along…we were saving money, off to Bali, then off for Christmas, and then, as our year was winding up, the building’s official deadline began to creep closer. Naturally, to speed things along, they hired an elevator operator to act as cleaning manager. Her name was Hanna, but with her accent she pronounced it “Huna”, and the others called her “Huna Muntuna”. She was given a clipboard and it made her drunk with power, why not just give her a loaded gun? She started coming by everyday and began to nit-pick. Prior to this, I had been dealing with men, and generally are much easier to convince that something is perfectly clean…when it’s really not. But it really was an impossible job with improbable expectations. All the other workers that came before made such a mess, so as the last person working in a ‘finished’ space, I failed before I even began. If jobs took an unreasonable amount of time because of the tilers or the painters, I would claim my piece rate fee, but also take an hourly wage for the extra time spent. I fought for that rate–went to the manager of that site and demanded it and he allowed it.

But Huna Muntuna didn’t think that was a good deal. “You see Alicia…that’s what we call ‘double dipping’ in this business”. She’s standing in the doorway, and I am perched on a rickety ladder, wearing a vac-pak, (imagine if a vacuum cleaner and a back pack had a baby), and she is threatening the nice little routine I have made for myself. “It’s not coming out of your pocket Hanna…I work hard, and I wouldn’t make any money otherwise”. She studied the clipboard, and gives me this pained look that said “I’d love to help you, but I don’t want to”. This whole conversation took place while I was on the ladder, dressed as a hoovering Quasimodo. I felt this singular angry drop of sweat roll down my side. I stepped off the ladder, and let the vac pack fall to the ground. “Hanna…you’re not going to change a thing, you don’t have to worry about me”. Ben had told me when I started the job that I had to be ‘stroppy’, be tough and no tears. This was the crowning achievement, my coming down to her level and fighting for my bread and butter. Did I yell? Yes. Did I cry? Absolutely. What did she know about my work? Nothing. Though she claimed she came from a family of cleaners–maids begetting janitors, like generations in the bible, she was still unaware of the work that was happening in this very room.

After I shouted and sobbed, Huna Muntuna generally left me alone. The days in the country were winding down, and I had a week left to go. She came to check on me one afternoon and was picking out something “that didn’t feel quite clean” that was only reachable if you were to rip a limb from your body and jam it under the sink and right up under into the ledge just behind the plumbing. I felt that white hot rage of managerial injustice, and then I try to reason with her…but asking her questions about her life, and by telling her about myself. I ask her where she’d like to travel if she could go anywhere: “Alaska”, she decided “Yea, I saw a show on it once, looks real mean (read-”cool’). “Well, I’d really like to go to Europe eh?” I say to her “I love the idea of all those countries clustered together”–”Yes, one minute you’d be in Paris, next minute you’d be in France”. “They are quite close”, I smiled. And just like that all my anger fell away. She can have the have her clipboard and authority, this is not the last job I’m ever going to have, and Hanna would always be in the exact same place. On my last day of work, I was nervous that she would not sign off on my last floor. Glory be, the Gods were smiling on me, and it turned out that she had called in sick, and I was elated to finish my job in solitude. At the end of the day, Ben and I went to the roof of the building and looked over the cityscape, all the pools down below, the palm trees, the blue water. There was this moment of quiet, as we examined the view. All these images and possibilities that was far beyond reach. We were not yet home, we were somewhere in the middle, like Sisyphus the moment after he lets that boulder roll down the hill.

All Images Courtesy of Google

All Images Courtesy of Google

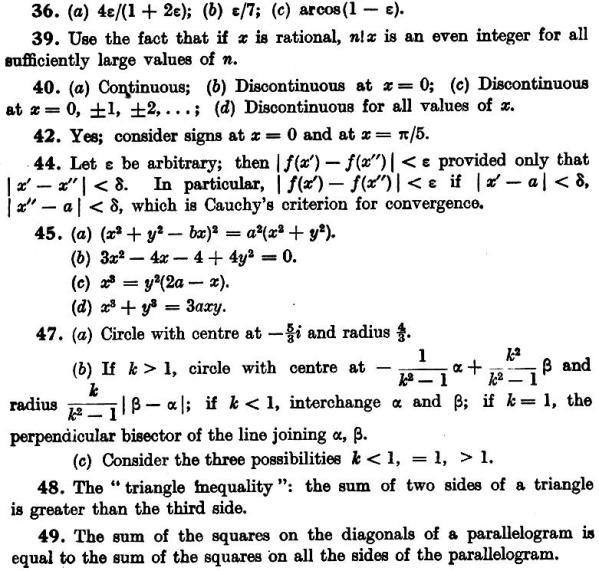

The orientation began, and there was no need to fill the space with any more questions. But I’m left wondering about x’s and y’s, and what those equations are about, and what they are for. And it makes me a little bit sad that I’ll never truly understand.

The orientation began, and there was no need to fill the space with any more questions. But I’m left wondering about x’s and y’s, and what those equations are about, and what they are for. And it makes me a little bit sad that I’ll never truly understand. All Images Courtesy of Google

All Images Courtesy of Google

All Images Courtesy of Google

All Images Courtesy of Google

All Images Courtesy of Google

All Images Courtesy of Google Some bastard pulls out in front of me, and I bark an obscenity out, mouth full of muffin. I catch a glimpse of my reflection.

Some bastard pulls out in front of me, and I bark an obscenity out, mouth full of muffin. I catch a glimpse of my reflection.

My god woman, how much wine did you spill?

My god woman, how much wine did you spill? iAll Images Courtesy of Google

iAll Images Courtesy of Google All Images Courtesy of Google

All Images Courtesy of Google

But I was only eight years old when this happened, so I only wished I looked like that. Hell, I’m 31 and would be hard pressed to pull off that Betty Grable getup.

But I was only eight years old when this happened, so I only wished I looked like that. Hell, I’m 31 and would be hard pressed to pull off that Betty Grable getup.

We were living and working in a fortuitous country, and in a short time, got ourselves a little slice of the pie. But while wealthy miners were winging to Bali for a quick weekend getaway; we were aware that this was not a throw away holiday. This was a once-in-a-lifetime adventure, and though we had to acknowledge staggering levels of poverty, all you could do was feel humble gratitude and tip extremely well. And we were determined to not let it get in the way of our good fortune. I even got a little sassy and stared roaming pool side with only a sarong wrapped around my waist. The angle of our pool was high up, and therefore, there was not a soul to see us. Until we realized that we had been putting on a pretty good show for some construction workers over the hill. Floating in the water, my legs wrapped around my husband, I noticed half-dozen or so men, crouching down and eating lunch and watching our watery antics.

We were living and working in a fortuitous country, and in a short time, got ourselves a little slice of the pie. But while wealthy miners were winging to Bali for a quick weekend getaway; we were aware that this was not a throw away holiday. This was a once-in-a-lifetime adventure, and though we had to acknowledge staggering levels of poverty, all you could do was feel humble gratitude and tip extremely well. And we were determined to not let it get in the way of our good fortune. I even got a little sassy and stared roaming pool side with only a sarong wrapped around my waist. The angle of our pool was high up, and therefore, there was not a soul to see us. Until we realized that we had been putting on a pretty good show for some construction workers over the hill. Floating in the water, my legs wrapped around my husband, I noticed half-dozen or so men, crouching down and eating lunch and watching our watery antics.